orienting around

Yeşim Akdeniz & Marwan Bassiouni

Dürst Britt & Mayhew, Den Haag

Edward Said’s book ‘Orientalism, Western Conceptions of the Orient’ (1978) was groundbreaking when it came out, and still reverberates in post-colonial discourses today. Said described the dynamics of Orientalism: the image of the East created by the West (the Occident), and most notably Europe. Rather than a true representation of cultures in ‘the Orient’, the cultural production that we call Orientalism is a depiction of the East for a distinctly Western market that thrives on clichés and stereotypes — to be found in etchings

of harems in the 19th century as readily as discourses on immigration in newspapers today.

Dürst Britt & Mayhew shows two artists who relate to this discourse in

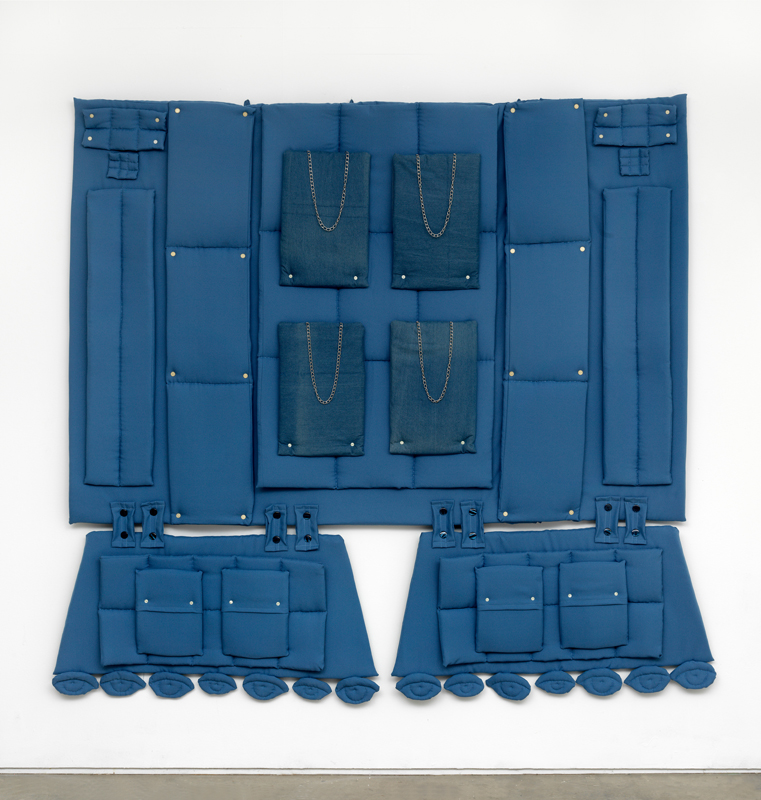

very different ways. Through his photographic work, Marwan Bassiouni (1985, Switzerland) seeks to create a representation of the Islam in the Netherlands that corresponds with his own experience as a practicing Muslim. His documentary photos portray the interiors of Dutch mosques simultaneously with the views we can see through their windows. Yeşim Akdeniz (1978, Turkey) formulates a new imagery that expresses the ways in which her identity is shaped by Orientalism and other power relations. She has recently expanded her painting practice to big sculptural textile works, which evoke feelings of familiarity and intimacy as well as bondage and uniformity. Both artists work in their own way to untangle and understand how the European gaze has influenced their identities and cultural production as ‘orientalised’ artists, and have developed strategies to negate that gaze.

Orienting around

In Marwan Bassiouni’s ‘New Dutch Views’ the landscape outside is as crisp and bright as the interior framing it, meticulously exposing the reality of the outside world as well as any minor detail in the mosque. Bassiouni achieves this impossibly equal distribution of light through combining several exposures in one image, causing neither foreground or background to be favoured. The oriental motifs in the decorations of the mosque would still seem distinct from the sometimes bleak, sometimes picturesque, but always unmistakably Dutch views outside, if not for banal details like a luxaflex, a light plug or a heater. It’s tempting to analyse the photos, since they literally reveal something about the position of Islam in Dutch society. There is not just one ‘typical’ location, however, something that Bassiouni is quick to confirm. The mosques are built — or get established in repurposed buildings — in industrial areas, in the middle of fields, next to train tracks and in the middle of city centers. If there is anything typical it would be the plethora of grey carpets and suspended ceilings in the interiors, dating many spaces back to the 1980s at most. A timeline which roughly follows the history of immigration itself.

1.

When Bassiouni graduated from the KABK in 2018 with New Dutch Views, his work quickly gained traction. Born in an Egyptian American Muslim household in Switzerland, it was not until the age of twenty-four that he began to take interest in Islam. He told me that his photography and religious practice went their own ways, until he found it increasingly important to convey his knowledge of Islam as a response to its perception in society

and its portrayal he encountered in the media. His work both depicts a representation of Islam and is an artistic practice departing from Islamic values. Different from the tendency to see artists as separate from their work, he has become inspired by the way Islamic calligraphers were not

said to strive to make beautiful work, but rather practice being a certain, virtuous, way. The work would naturally follow. It is not immediately evident that the metaphysics of religion would be represented in such realist

photos. Like Judaism and some forms of Christianity, however, Islam does not accept representation of The Divine, since the sacred is beyond not only description but beyond comprehension. In that sense, Bassiouni searches for transcendence in the beauty of the banal. As he explained to me: ‘You can’t represent the sacred, the invisible. The sacred is within the person looking and everything created’.

Edward Said describes Orientalism as a way of speaking, thinking and writing that affords the West an Other in contrast to whom the identity of the West can be constructed. In her book ‘Queer Phenomenology’ (2006), theorist Sarah Ahmed explains this argument from the perspective of orientation.

As she explains it, it is not a coincidence that the word ‘orientation’ refers both to the practice of establishing one’s direction and to the East itself as one direction. Simply put: the West has a long history of orientating itself by looking at the East. The West’s obsession with the orient should be seen as a way to constitute itself by looking at the ‘other’ as not-itself. ‘A

“we” emerges as an effect of a shared direction toward an object’, Ahmed specifies. ‘The Orient here would be the object toward which we are directed, as an object of desire. By being directed towards the Orient, we are orientated “around” the Occident. The Occident coheres as that which we are organised around through the very direction of our gaze toward the Orient’. For the Occident, for Europe to shape itself, its orientation was towards the Orient. When looking at Bassiouni’s work, we can see how looking at the Dutch landscape through the gaze of the mosque is in that sense a radical gesture, a reversal of the Occident’s obsession with the East. Instead of the West’s Orientalism, Bassiouni makes us look at the Netherlands, in exploration of his identity as a muslim.

Bassiouni’s ‘Prayer Rug Selfies’ are another depiction of the daily life of religious practice. This series shows the small rug, just after Bassiouni’s prayer. The position of the camera in relation to the rug is oblique, we don’t follow its orientation towards Mecca but approach it slightly from the side. Bassiouni just stepped away from the prayer rug to take the photo, one can sense that there is still a presence lingering there, in some photos he has left his shoes behind. Throughout the series, the position of the rug is exactly the

2.

same. Looking at a few it becomes almost invisible through repetition, and the attention is drawn to the variety and difference in environments that the prayer takes place: the open forest, a museum, a bathroom, a parking lot, a storage space. These spaces, unexpected in their familiarity, support Bassiouni’s desire to show that nor the Islam, nor Muslims, have one form.

Layering

Where Bassiouni approaches the portrayal of the Islam from a religious perspective, Yeşim Akdeniz addresses Orientalism from a secular perspective, intersecting with critical reflection on racism, gender and the patriarchal systems in Europe as well as in the East. Akdeniz is known as a painter. With her new series ‘radical selfcare’ she explores textile work as a new extension of painting and as a refection on the medium, as well as offering new ideas on identity formation. The title of Akdeniz’ series was inspired by Audre Lorde’s famous essay ‘A Burst of Light: Living with Cancer’ (1988), in which she writes:

‘Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare’. As a Black Lesbian, the care of Lorde for herself as a marginalised identity was an act of resistance in itself. According to Akdeniz, other than the consumerist connotation of the term ‘self-care’ today, radical selfcare is ‘the fight to accept and preserve your identity, so that you can resist the patriarchy and all the norms that you want and need to oppose’.

Until now, the majority of works in the ‘radical selfcare’ series have been titled and numbered ‘selfportrait as an orientalist carpet’ which Akdeniz intended as an ironic wordplay on the classic oriental carpet: the most widely appropriated object of ‘oriental’ culture. The addition of ‘Orientalist’, however, means that this particular carpet is not from ‘the orient’ but rather from Orientalism, the production of the East by the West. As Sarah Ahmed writes, the arrival of objects is always a result of orientation. ‘If we rethink domestic space as an effect of the histories of domestication, we can begin to understand how “the home” depends on the appropriation of matters as

a way of making what is not already familiar or reachable.’ Akdeniz’ work is invested in understanding how objects like the oriental carpet slide from one cultural register into another, whether through appropriation from the East to the West or through other movements. She enthusiastically describes

the way that her shift from painting to textile work has changed the shops in which she buys her material. From expensive painting specialty shops that correspond with the ‘high culture’ in which painting has historically been situated, she now buys at ‘haberdashery shops’ which sell small articles

for sewing, such as buttons, ribbons and zips. This intersection between Orientalism and economic class expresses itself in her latest work, ‘mistrust of the suburban’ (2021), a room screen which brings to mind the relationship between the bourgeoisie and the domestication of objects from ‘the Orient’. Room screens became very popular in bourgeois households in the mid 19th century after Europe forced Japan to open up its international trade in 1859, after being cut off from almost all international contact for two centuries.

3.

Akdeniz points to the fact that the long history of Orientalism has caused the East to start looking at itself differently. This internalisation of the orientalist gaze complicates the notion of a self-portrait, which is reflected in the layered imagery of the work, which indeed doesn’t look like any conventional idea of a self-portrait at all. The pockets and mostly monochrome colours suggest uniformity and the straps, buckles and ropes that attach or shape the volumes, evoke the feeling of constraint and power relations. The material of the ‘radical selfcare’ series nods to the gendered and feminist histories of textile work, but by making them large and looming as they are Akdeniz has made sure to strip them from any cuddly feelings. Tassels and eyes suggest the kind of decorative details that are immediately legible as

‘oriental’, although they are for sale in any tourist shop, or on any pillowcase. Throughout the work, Akdeniz slides between registers: painting and sculpture, intimacy and violence, appropriation and identity, performance and representation. The pillows and pockets seems real enough, but they are alternated with two-dimensional pumpkins and suitcases in clumsy perspective. The pockets turn out to be fixated, and are not pockets at all.

In the end, the works literally carry many layers of at least 25 meters of textile, which — if not for their strong fabric — would be at risk of tearing because of their heavy weight. Would the work of radical self-care be to inspect each and every layer, or is the work to preserve and hold it all?

When I ask Akdeniz on the matter of perspective and the gaze, in relation to Bassiouni’s work, she says: ‘My work is not a window to anything, I am interested in creating my own vocabulary.’ Rather than a clear perspective on any subject, the textile works of Akdeniz represent the entanglement of different identities represented by cultural objects.

Bassiouni gives us a the feeling of a clear perspective on both the mosque and the Dutch landscape outside, while Akdeniz’ works have many layers and hidden pockets, which don’t seem to travel anywhere but their own symbolic entanglement. Thinking through Sarah Ahmed’s theory on orientation, both Bassiouni and Akdeniz propose a re-orientation of the ‘orientalised’ self as the subject, rather than serving as an horizon to someone else’s orientation.

—

Pia Louwerens is an artistic researcher, artist and writer. She has completed

a post-master and fellowship program at a.pass (advanced performance

and scenography studies), Brussels. In 2021 she self-published her book ‘I’m Not Sad, The World Is Sad’, an autotheoretical, semi-fictional account of the increasingly paranoid relationship between an artistic researcher and the art institution where she is ‘embedded’. Next to her artistic practice Louwerens has written texts for a.o. De Witte Raaf, Metropolis M, Tubelight and Het Parool. Pia Louwerens lives and works in Brussels.